Elisabeth did pioneering work on the themes of death and dying. She sometimes caused controversy, but her work helped people to talk about death, one of the certainties of life.

The two videos in this article were filmed in 1975. They show her speaking to medical staff about her experiences working with dying patients.

Born in Switzerland, Elisabeth qualified as a doctor at the University of Zurich. It was there she met her future husband, Emanuel Robert Ross. In 1958 she moved to the United States where she spent much of her life.

Working in hospitals during the 1950s and 60s, she became concerned about the treatment of dying patients. She later said:

“They were shunned and abused; nobody was honest with them.”

Elisabeth began spending more time with terminally ill patients.

She became known for this work and was asked to give a lecture on death and dying. This provided to be a turning point.

Abandoning the traditional practice of reading notes from behind a lectern, she invited a dying woman to share the platform and talk about her feelings.

This shocked the professionals, but the woman was at ease talking about her approaching death.

Elisabeth was invited to run similar sessions across the country. She embarked on a series of workshops for mixed groups: people who were dying and people who were caring for the dying.

‘Helpers’ learned from patients and, by coming to terms with their own deaths, people learned to live more fully.

She published her book On Death and Dying in 1969 and travelled across the globe. Newspapers, magazines and the media ran stories about her work. At that time there was still a taboo regarding talking about dying.

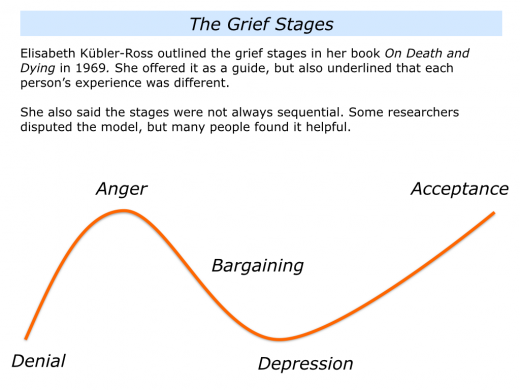

Elisabeth is known for her work on the stages of grief. She described the following stages that people often go through when facing the prospect of death or what they perceive to be a negative transition.

Starting from feeling relatively stable, they then embark on the following stages.

Denial: “This can’t be true.”

Anger: “Who is to blame?”

Bargaining: “If things work out, I promise to live a better life.”

Depression: “This is awful. I can’t see a way forward.”

Acceptance: “I am ready to move on.”

Elisabeth explained that the phases were not necessarily sequential and people might go through some, but not all, of the stages.

There would be up-and-downs – regressions and leaps forward – because the process is not linear.

Some researchers challenged the model, but many people found it gave a framework for making sense of their experience.

This was in itself liberating. Like many epiphanies, it started with the person realising:

“Now I can see what is happening. It isn’t only me who feels this way.”

The Grief Cycle Model was developed and adapted by other people.

Anybody who has been on a Change Management or Transitions Management course will have seen various adaptations.

Elisabeth went on to do other work, particularly in relation to: ‘What the dying have to teach the living’.

But she will probably be remembered most for the five stages of grief. This gave people strength to talk about one of the last taboos.

Below is a video to a link that shows Elisabeth talking with a dying patient. It is powerful and heart-wrenching.

Though full of sorrow, the video also contains some beautiful moments.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=tIZ97OALEfE

Here is a link to site dedicated to her life and work.

Leave a Reply