Friedrich Froebel did positive work by being an educational pioneer who gave birth to the kindergarten – ‘the children’s garden’.

He believed children needed a place where they could be cherished, stimulated and helped to flourish.

His ideas were adopted by many ambassadors who spread the methods across the globe.

These influenced the upbringing of people such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Buckminster Fuller, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Enid Blyton and Bertrand Russell. You can discover more about the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and Paul Klee, for example, via the following links.

https://www.artsy.net/artist/frank-lloyd-wright

https://www.davidzwirner.com/artists/paul-klee

There are several sites that provide an in-depth exploration of Froebel’s work. One of most comprehensive is the Froebel Web – see link below.

(The name Froebel is pronounced in many different ways by German speakers. English speakers usually say Frurbel – to rhyme with herbal or Froy-bel.)

Philosophy and Background

Today the word ‘kindergarten’, first used by Friedrich Froebel in 1840, is accepted as part of everyday language.

But it can be useful to review the principles which inform Froebel’s approach to early years education.

For more than a century these have informed the training of early years teachers at Froebel College, which was established at West Kensington, London, in 1892. It moved to Roehampton in 1922.

The College, now part of Roehampton University, continues to educate teachers from around the globe. The principles are summarised here:

Elements of a Froebelian Education

for Children from Birth to Seven Years

1) Principles which include

* recognition of the uniqueness of each child’s capacity and potential

* an holistic view of each child’s development

* recognition of the importance of play as a central integrating element in a child’s development and learning

* an ecological view of humankind in the natural world

* recognition of the integrity of childhood in its own right

* recognition of the child as part of a family and a community

2) A pedagogy which involves

* knowledgeable and appropriately qualified early childhood professionals

* skilled and informed observation of children, to support effective development, learning and teaching

* awareness that education relates to all capabilities of each child: imaginative, creative, symbolic, linguistic, mathematical, musical, aesthetic, scientific, physical, social, moral, cultural and spiritual

* parents/carers and educators working in harmony and partnership

* first hand experience, play, talk and reflection

* activities and experiences that have sense, purpose and meaning to the child, and involve joy, wonder, concentration, unity and satisfaction

* an holistic approach to learning which recognises children as active, feeling and thinking human beings, seeing patterns and making connections

* encouragement rather than punishment

* individual and collaborative activity and play

* an approach to learning which develops children’s autonomy and self confidence

3) An environment which

* is physically safe but intellectually challenging, promoting curiosity, enquiry, sensory stimulation and aesthetic awareness

* demonstrates the unity of indoors and outdoors, of the cultural and the natural

* allows free access to a rich range of materials that promote open-ended opportunities for play, representation and creativity

* entails the setting being an integral part of the community it serves, working in close partnership with parents and other skilled adults

* is educative rather than merely amusing or occupying

* promotes interdependence as well as independence, community as well as individuality and responsibility as well as freedom.

You can find more details about what is now the Froebel Trust here.

http://www.froebeltrust.org.uk/

Influences

Froebel was an innovator, who was influenced by the key pioneers of education John Amos Comenius and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. Let’s explore their contributions.

John Amos Comenius

Comenius, who lived from 1592 to 1670, was a Moravian theologian and educator who became bishop of the Unity of Brethren.

Travelling all over Europe, he dedicated himself to helping students to learn. He also implored people to recognise they were part of one human family – rather divide over national rivalries.

Comenius is considered by many to be ‘the father of modern education’. He believed in providing education for all children – both girls and boys – not just those from richer families.

He produced the first picture book for children and his books were translated into the major European Languages.

His ideas were particularly well received in Northern Europe. He was invited, for example, to restructure the entire Swedish education system.

Here are some of the best known quotes from his book The Great Didactic (sometimes known as The Whole Art of Teaching.)

“The proper education of the young does not consist in stuffing their heads with a mass of words, sentences, and ideas dragged together out of various authors, but in opening up their understanding to the outer world, so that a living stream may flow from their own minds, just as leaves, flowers, and fruit spring from the bud on a tree.”

“(Learning is natural) … Who is there that does not always desire to see, hear, or handle something new? To whom is it not a pleasure to go to some new place daily, to converse with someone, to narrate something, or have some fresh experience?”

“In a word, the eyes, the ears, the sense of touch, the mind itself, are, in their search for food, ever carried beyond themselves; for to an active nature nothing is so intolerable as sloth …”

“We are all citizens of one world, we are all of one blood. To hate a man because he was born in another country, because he speaks a different language, or because he takes a different view on this subject or that, is a great folly. Desist, I implore you, for we are all equally human …

“Let us have but one end in view, the welfare of humanity; and let us put aside all selfishness in considerations of language, nationality, or religion.”

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was another influence on Froebel. Living from 1746 to 1827, this Swiss educator believed in offering all children the opportunity of a good education. He thought it was vital:

To recognise that each child’s personality is sacred.

To provide a safe environment in which children could learn (no flogging!).

To include the five senses in the learning process. He believed it called for providing learning that connected the hand, heart and head. This also meant learning both indoors and outdoors.

To start with concrete work – then move to abstraction. This called for an emphasis on learning by doing, clarifying the thinking and then practicing. He believed in encouraging children to think for themselves.

To recognise that love of learning will continue to drive the learning.

Pestalozzi explained his approach in a book called How Gertrude Teaches Her Children: An attempt to help mother to teach their children and an account of the method.

This attracted wide attention and students flocked from many countries, one of these was Froebel. Before looking at how Froebel developed his own ideas, however, let’s explore his background and development.

Growing up

Friedrich was born in April 1782 at Oberweissbach, now part of Thuringia in Central Germany. He had a difficult childhood.

The son of a pastor, he was sixth child in the family. He was less than a year old when his mother died and 4 years of age when his father remarried.

He failed to get the love he wanted from the family. His stepmother addressed him in an impersonal way. She used the formal term ‘Sie’, rather than the informal ‘Du’ (You).

His loneliness was lifted at the age of 10 when his biological mother’s brother, Johann Cristoph Hoffman, invited him to Stadtilm and took over his care. Friedrich later wrote:

“It was first in Stadtilm where balance came back into my life, because at home I had found neither motherly love nor fatherly affection.”

Friedrich took a job as a forester when he was fifteen. This proved life-changing.

Observing the plant and animal life, he experienced a sense of wonder. Flora, fauna and animals grew in an organic way with the whole eco-system achieving a certain unity.

Surely the same could be true for human beings? Froebel saw the interconnectedness in what he believed to be God’s universe. This was a theme that would arise in his later teachings.

Finding his calling

Enrolling at the University of Jena when he was 17, Friedrich looked forward to his studies.

Unfortunately the lessons were sterile and, despite switching courses, he found little satisfaction.

Eventually poverty forced him to leave university. Despite owing people only a small sum – 30 Taler – he spent time in a debtor’s prison.

Moving on, he spent the next four years trying many different kinds of work, finally deciding to study architecture at Frankfurt. During this time he met Anton Gruner, who ran a school in the city.

Gruner was a follower of Pestalozzi and, seeing Friedrich’s potential, suggested that he become a teacher.

Froebel was in his element. He had finally found his calling.

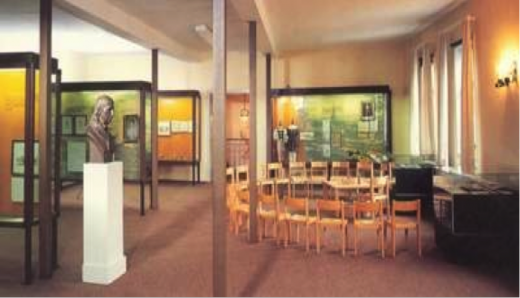

The Froebel Museum

Developing his ideas

Friedrich taught for a while and then 2 years studying at an institute run by Pestalozzi.

Whilst he found the approach inspiring, he had some reservations. So he vowed to create his own type of school.

During the next few years he pursued other activities – such as studying mineralogy and serving for the Prussian army against Napoleon – but he kept returning to his dream. Froebel’s education actually benefited from both these activities.

Recalling his study of crystals, he said later: “The world of crystals proclaimed to me in distinct and unequivocal terms the laws of human life.”

Whilst serving in the army he also made two friends, Heinrich Langenthal and Wilhelm Middendorf. Both would help him in his future educational work.

Friedrich spent the years between 1816 and 1840 developing his ideas. During this time:

He founded a school in Thuringia. Departing from the prevailing practice in ‘ordinary schools’, it also offered education to children under six.

Froebel was joined there by several devotees, including Langenthal and Middendorf. The teachers’ families lived together in a community and the school’s approach was based on enabling pupils to develop their creativity.

He married Henriette Wilhelmine Hoffmeister. The marriage lasted 21 years until her death in 1839. (He would marry again in 1851 to Luise Levin.)

His ideas also began to reach a wider audience. He published The Education of Man and designed educational materials that encouraged children to use their creativity.

Friedrich was invited to Switzerland and spent several years there opening schools. Returning to Bad Blankenburg, he founded the Play and Activity Institute and trained play facilitators.

He also developed more of the ‘play gifts’ – educational materials for children.

The Froebel Web explains:

“The materials in the room were divided into two categories: ‘gifts’ and ‘occupations’ or activities.

“Gifts were objects that were fixed in form such as blocks. The purpose was that in playing with the object the child would learn the underlying concept represented by the object.”

“Occupations or activities consisted of material that children could shape and manipulate such as paper, clay, sand, beads, string etc.

“There was an underlying symbolic meaning in all that was done. Even clean up time was seen as ‘a final concrete reminder to the child of God’s plan for moral and social order.’”

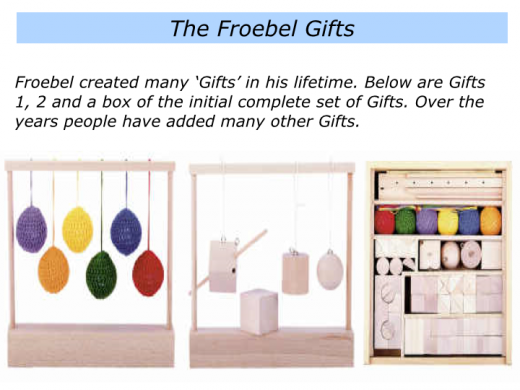

The ‘Gifts’

Froebel is probably best known: a) for creating the ‘kindergarten’; b) for creating ‘gifts’ – what would now be called ‘educational materials’ – for children.

(The original German term for each ‘Gift’ is ‘Gabe’. So in Froebel literature you will see references to ‘Gabe 1; Gabe 2;’ etc.)

He produced gifts that were ‘simple’ and interrelated. They encouraged the child to play, be creative and explore designs that mirrored the unity of the universe.

So what were the gifts? The following material is drawn from the Froebel Web and can be found at:

Froebel Gifts – uncovering

the orderly beauty of nature

“The original five gifts were published by Froebel in his life time. The remaining gifts were used by Froebel in his Kindergarten and published after his death …

“Collectively they form a complete whole, like a many branched tree, whose parts explain and advance each other.”

“Each is a self-contained whole, a seed from which manifold new developments may spring to cohere in further unity.

“They cover the whole field of intuitive and sensory instruction and lay the basis for all further teaching.

“Froebel developed a specific set of 20 ‘gifts’ – physical objects such as balls, blocks, and sticks – for children to use in the kindergarten.

“Froebel carefully designed these gifts to help children recognize and appreciate the common patterns and forms found in nature. Froebel’s gifts were eventually distributed throughout the world, deeply influencing the development of generations of young children.”

The first gift – a ball.

“This is the first and most important plaything of childhood. The child first seeks to contemplate, to grasp and to possess objects as a whole.

“A ball supplies exactly what the child seeks, and so the child likes to play with the ball. The extraordinary charm of a ball exerts a constant attraction both in early childhood and later youth.”

The second gift – the sphere and the cube.

“This gives more pleasure than the ball during the second half of the first year, when children begin to employ themselves in more definite ways.

“The sphere and cube belong together in play because they are opposite and alike.”

The third gift – a wooden cube, divided once in each direction to create eight smaller cubes.

“The cube of the second gift is the basis of the third gift. Eight cubes are presented to the child in the form of a single larger cube.

“As each cube is removed, different shapes emerge.” The eight blocks can then be arranged to create forms of life, knowledge and beauty. These involve:

Forms of Life

The child can use the gifts to create something they find in their life – such as a building, house, table, sofa or tree.

Forms of Knowledge

The child can use the gifts to explore maths, science and logical ideas. This enables them to develop their sense of proportion, equivalence and order.

Forms of Beauty

The child can use the gifts to create beauty. The Froebel Web explains:

“The blocks can be arranged to form patterns of symmetry and harmony. Beauty forms appeal to our aesthetic sense. Froebel also called this dancing as the blocks are progressively rearranged to reveal evolving patterns of increasing complexity.”

The fourth gift – is a cube of the same dimensions as the third gift.

“It also consists of eight identical blocks, each of the same volume as the blocks of the third gift.

“The blocks in this gift are each twice as long and half the thickness of the cubes of the third gift … Together with the blocks of the third gift more complex Life Forms emerge.”

The fifth gift – this gift expands on the cubes of the third gift.

“Presented as a larger cube with three blocks along each edge, it would theoretically consist of twenty seven cubes.

“The surprise in this gift is that three of the cubes are divided diagonally to form six triangular faced blocks and another three are divided twice to form twelve smaller triangular blocks.

“The triangular shapes also enable the construction of more complex Beauty and Life Forms.”

Froebel’s innovative work attracted admirers and critics, the former helping him to take the next step.

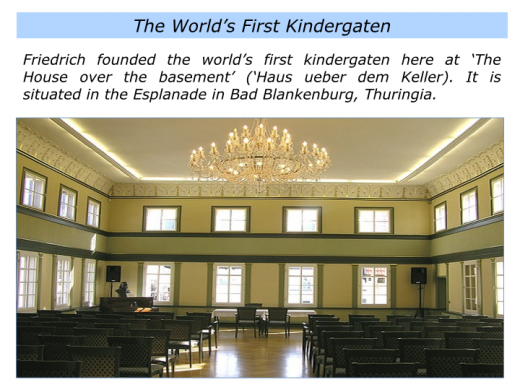

The Kindergarten Movement

Friedrich established the first Public Kindergarten in ‘The House over the basement’ in the Esplanade in Bad Blankenburg.

He coined the term ‘Kindergarten’ to emphasise the need to encourage children to grow. He said:

“Children are like tiny flowers; they are varied and need care, but each is beautiful alone and glorious when seen in the community of peers.”

Writing in his book, A Child’s Work: Freedom and Guidance in Froebel’s Educational Theory and Practice, Joachim Liebschner explains that there was one further key element:

“A long strip of land, in front of the house, became an essential part of the Kindergarten.

“The plan drawn up by Froebel himself and still in existence, shows a central area divided into single plots of about a square yard (square meter), one for each child, surrounded by a path and adjoined by similar size plots for growing flowers, fruit and vegetables.

“On either side of the central area were playgrounds for the children and overlooking all this, a paved area for visiting parents and friends of children.”

“While each child was free to arrange his or her own patch to grow what interested him or her, the enclosing beds were communally worked, thus emphasising the uniqueness of the individual as well as his or her responsibility toward the community.”

Froebel’s ideas were backed by influential people, many of the strongest advocates being women. Within a decade there were over 50 kindergartens established across the country.

The ideas also began spreading abroad – more of which later. During this time Froebel started a publishing firm for his books and educational materials.

His book Mother Songs proved enormously popular. Describing the book, the Froebel Web explains:

“It is a little universe, a Unity in itself. Froebel wanted to sum up his thoughts on education in this book.

“Froebel describes family situations from the daily life in a family … (The book) has a motto for each picture and then a verse for mother and child. Froebel also wrote commentaries to the pictures.

“The pictures, verses, rhymes and music should give the child an idea (Ahnung – a hunch or presentiment) of an inner world, that is from the outer to the inner.

“One of the purposes of the book was to develop a child’s ‘body, limbs and senses’ in various finger plays and games with its mother.”

During these years Friedrich established the first training institute for kindergarten teachers at Marienthal.

This was previously a hunting lodge of the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen, near Bad Liebenstein in Thuringia.

Upon seeing it for the first time, Froebel said:

“This would be a beautiful place for our institution. Marienthal, the vale of the Marys, whom we wish to bring up as the mothers of humanity, as the first Mary brought up the Saviour of the World.”

Success had its price, however, and the kindergarten movement was about to suffer suppression.

Froebel’s approach to education was perceived as radical, but the Prussian authorities confused his views with those of his cousin, a fiery socialist.

As a result, Prussia banned kindergartens from 1851, one year before Froebel’s death. The ban remained in place until 1860. Fortunately for the kindergarten movement, however, influential people carried the ideas abroad.

Many of these pioneers were women. Here are just a few who carried the torch.

Henriette Schrader-Breymann

Henriette worked with Froebel when he was in Thuringia and became one of the key educators in the kindergarten movement.

She went on to found the Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus, which still exists today. (See link at the end of this piece.)

Blazing the trail in a previously male-dominated culture, she developed a training centre for women teachers.

She combined theoretical training with hands-on experience – an approach that continues to this day. Henriette educated women from many different countries including, for example, the first Swedish Kindergarten teachers.

You can read about today’s work at Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus at:

Baroness Bertha von Marenholtz-Buelow

Connected to aristocratic families across Europe, she became a great advocate of Froebel’s methods.

She was a driving force in spreading his ideas to the Netherlands, England, France, Belgium, Italy and, through a relative, to the United States.

The Baroness used her aristocratic contacts when kindergartens were banned in Prussia and other German states.

Her efforts helped to lift the ban and she reached a wide audience by publishing her book Reminiscences of Froebel.

Margarethe Meyer Schurz

Margarethe was born into a prominent family in Hamburg. She was encouraged by her parents to pursue the arts and education.

During this time she came into contact with Froebel’s teachings and, together with her sister Bertha, met him in 1849. Bertha went on to open several kindergartens in Germany.

Moving to England with her husband, Mr Ronge, Bertha opened the England Infant Garden in Tavistock Place, London.

Margarethe joined her sister to teach in England before moving to Wisconsin with her husband Carl Shurz. Her story is continued on the Froebel Web at:

“Margarethe employed Froebel’s philosophy while caring for her daughter, Agathe, and four neighbour children, leading them in games and songs and group activities that channelled their energy while preparing them for school at the same time.

“Other parents were so impressed at the results that they prevailed upon Schurz to help their children, so she opened a small kindergarten, the first in the United States.

“Like most of the early kindergartens in the United States, it was conducted in German. The kindergarten in Watertown continued until World War I, when it was closed because of opposition to the use of the German language.”

“She later said that Froebel credited her with expressing his views better than his own books had.

“Her work certainly gained an audience; kindergarten became an accepted and integral part of American education and an accepted course of study for elementary teachers.”

“Margarethe Meyer Schurz died in Washington, D.C., at the age of 43. The memorial tablet, dedicated in 1929, rests only a few feet from the site of the building where she ran her kindergarten – the first ever in America:

“In memory of Mrs. Carl Schurz (Margarethe Meyer Schurz) Aug. 27, 1833 – March 15, 1876, who established on this site the first kindergarten in America, 1856.”

Elizabeth Peabody

Elizabeth was 55 when, in 1859, she learned of Froebel’s work in Germany. The next year she opened America’s first English speaking kindergarten in Boston.

She ran the school for 8 years and then made a study tour of Europe. Returning to the United States, she spread the message through her writing.

She wrote the Kindergarten Guide, Kindergarten Culture, The Kindergarten in Italy and Letters to Kindergartners. Elizabeth published the Kindergarten Messenger – the newsletter for the movement.

She also founded the American Froebel Union in 1877 and became its first president.

You can find out more about Elizabeth via the Google Reader excerpts of Women in American Education: 1820 – 1955, by June Edwards. This can be found at:

Death

Friedrich continued to pursue his ideas, but the final years of his life were difficult. Despite encouragement from his followers, he was dispirited by the ban on kindergartens in Prussia. He died on June 21, 1852 in the Marienthal.

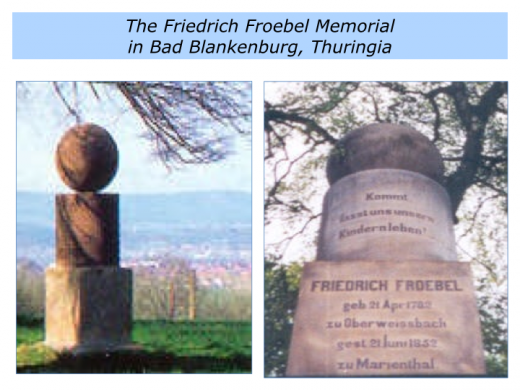

His final resting place is in Schweina near Bad Liebenstein. His grave stone was based on the ‘gifts’ of the sphere, cylinder and cube. The Froebel Web explains:

“The sphere and the cube together represented Knowledge, Beauty and Life.

“The sphere predominantly corresponds with the feelings or heart, (affective) and the cube to thought and intellect (cognitive).”

The Kindergarten Ban in Prussia was lifted in 1860, eight years after his death. Friedrich’s work lives on, however, in many places around the world.

Principles

Writing about Froebel, Baroness Bertha Marie von Marenholtz-Bülow explained how his personality lit up when engaged in his vocation. She wrote:

“He became entirely another person when his genius came upon him; the stream of his words then poured forth like fiery rain.

“It often came quite unexpectedly and on slight occasions; as in our walks, for instance, the contemplation of a stone or plant often led to profound outbursts upon the universe.”

“But the foundation of all his discourses was always his theory of development the LAW OF UNIVERSAL DEVELOPMENT applied to the human being …

“One needed to see Froebel in his class, in order to realize his genius and the strong power of conviction which inspired him.”

Bearing this in mind, let’s explore some of the principles that inspired him in his work.

People are creative

“Man is a creative being,” proclaimed Froebel. Everybody is creative, everybody is an artist.

Everybody can use their talents to shape a better world. Froebel believed that each person was many sided.

He used the analogy of a crystal. Shining a light on one side – providing one educational ‘gift’ for growth – may or may not highlight their brilliance.

Providing many educational ‘gifts’ gave opportunities to find and develop their talents. This could help people to follow a fulfilling path in life.

“The maple wood blocks … are in my fingers to this day,” wrote Frank Lloyd Wright, in his autobiography.

“As a child, Frank had already shown an interest in building. So his mother, Anna, bought him a set of Froebel gifts when visiting the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy web site says:

“Wright’s mother attended the Exposition, and brought back with her a new educational tool: Froebel blocks.

“Developed as part of Friedrich Froebel’s new Kindergarten program, the “gifts” presented structured play activities using two and three dimensional geometric forms, patterns, and constructions.”

“Even in his later years, Wright fondly recalled building with the maple blocks.

“The geometric logic of his buildings, their massing, and pattern can be traced back to the time he spent with his Froebel blocks.”

You can find this piece at:

Frank Lloyd Wright

People are creative in different ways. Enid Blyton became a Froebel teacher, for example, and went on to write stories for children.

Not everybody can become a famous architect or author, but everybody has talents they can use.

People can be helped to develop

through play and other creative activities

Creative people retain a sense of play. They love to follow their passion, pursue possibilities and create finished products.

“There is nothing more serious than play,” we are told.

Froebel believed it was vital to give each child the opportunity to explore different materials, create new forms – of life, knowledge and beauty – and achieve a sense of completion.

Writing in The Education of Man, Froebel explained the purpose of play and the various ‘gifts’.

“Play is the highest expression of human development in childhood for it alone is the free expression of what is in a child’s soul …

“The character and purpose of these plays may be described as follows:

“They are a coherent system, starting at each stage from the simplest activity and progressing to the most diverse and complex manifestations of it …

“The purpose of each one of them is to instruct human beings so that they may progress as individuals and members of humanity in all its various relationships.”

“Collectively they form a complete whole, like a many branched tree, whose parts explain and advance each other.

“Each is a self-contained whole, a seed from which manifold new developments may spring to cohere in further unity.

“They cover the whole field of intuitive and sensory instruction and lay the basis for all further teaching.”

“The mind grows by self revelation. In play the child ascertains what he can do, discovers his possibilities of will and thought by exerting his power spontaneously.

“In work he follows a task prescribed for him by another, and does not reveal his own proclivities and inclinations – but another’s. In play he reveals his own original power.”

Froebel believed that each child had their own rhythm. They would learn when they were ready to learn.

The educator’s role was to provide the encouragement and stimulation to help them develop.

Play can be a starting point for creativity, but progress does not always come easily. Doing what you love can involve overcoming tough challenges. Froebel wrote:

“A child who plays and works thoroughly, with perseverance until physical fatigue forbids will surely be a thorough, determined person, capable of self-sacrifice.”

Creative people do what they enjoy but they also love to ‘sweat’. They gain a great sense of satisfaction from completing a task that adds to life, knowledge or beauty.

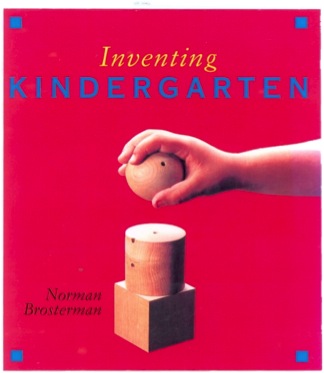

Norman Brosterman explores such creativity in his book Inventing Kindergarten: Seedbed of Modern Art. Looking at Froebel’s influence, he describes how kindergartens played a key part in the development of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus school. He argues for revisiting the original spirit of Froebel’s work.

He believes this produces “a sensitive, inquisitive child with an uninhibited curiosity and a genuine respect for nature, family and society.”

People can do creative things that mirror

and contribute to the unity of the universe

Froebel was a deeply spiritual man – seeing God’s hand at work everywhere in the universe. Perhaps he was born that way. Perhaps it came from his time as a forester, observing the patterns of nature.

Perhaps it came from his time as a mineralogist, observing patterns in crystals. Perhaps it was simply because he appreciated life.

Whatever the causes, he saw patterns in the universe. Froebel believed it was possible for human beings to experience, emulate and build on these designs.

Children could experience these patterns in kindergarten. The loving environment enabled them to feel safe and, like flowers, they could be nurtured to grow.

The ‘gifts’ replicated and gave children the opportunity to pursue the designs in life, knowledge and beauty.

The physical garden enabled them to connect with the eternal rhythms in nature. ‘Connection’ was a crucial element for Froebel. This meant connection with one’s soul, connection with other people and connection with the universe.

For him this also meant connection with God. Exploring and creating such designs could enable people to fulfil their potential. He wrote:

“If man is to attain fully his destiny, so far as earthly development will permit this, if he is to become truly an unbroken living unit, he must feel and know himself to be one, not only with God and humanity, but also with nature.”

Practice

So what have been the effects of Friedrich’s work? The word ‘kindergarten’ has become integrated into many languages.

Thousands of kindergartens have been set-up around the world. His work also had a strong influence on educational thinkers such as Thomas Dewey in America.

Now there are colleges that specialise in educating teachers in Froebel’s approach.

Peter Weston’s book The Froebel Educational Institute, for example, outlines the history and ongoing development of the Froebel College in the UK.

Peter has also produced an excellent overview of Friedrich’s influence in Friedrich Froebel: His Life, Times and Significance.

You can find a free download at:

The kindergarten movement enabled children to explore. It also encouraged many women to develop their professional careers. Let’s consider these two themes.

Kindergartens

The best kindergartens are real ‘gardens for children’. Researching for this article, I interviewed parents whose children attended Froebel kindergartens.

The response of one parent, Liz Straker, was typical. Looking back at the kindergarten her children attended, she said:

“The environment was stimulating. It offered variety and encouraged kids to be curious.

They would come in the morning and there would be at least 10 activities laid out for them to choose from.

“Kids could choose what they were interested in – not be told what to do. There was close observation of each individual child and their progress and needs.”

“The activities on offer would change daily. These might include dressing up, computer, some teacher-led arts, craft activity and role playing.

“There were also lots of outdoor activities with interesting equipment, such as mini-assault courses, gardening and bicycles.

“Sometimes there would be ‘Show and Tell’. Each child would bring something in they were interested in and talk to the rest of the class about it.

“There was a daily structure and timetable that was adhered to. Break time, group reading time and outside play time was at the same time each day.

“This gave the kids a sense of stability and security. Finally, they were encouraged to take responsibility – caring for each other and clearing up at the end of the day.”

“Sounds like how it should be,” somebody may say. Agreed, but therein lies a challenge.

The kindergarten described by Liz embodies the spirit of Froebel’s work. Some others simply put up the name ‘Kindergarten’.

They then failed to understand the philosophy about encouraging each child in the garden.

Manufacturers produced building blocks and other educational toys that were poor copies of the originals.

Froebel recognised the limitations of his own writing, which is maybe why he placed so much emphasis on training teachers.

Seeing him – and his nearest teachers – in action was the best way to convey the spirit behind the kindergarten.

Women Teachers

Froebel had an enormous effect in another area. He laid the foundations for many women to develop professional careers as kindergarten teachers. He wrote:

“The destiny of nations lies far more in the hands of women, the mothers, than in the possessors of power, or those of innovators who for the most part do not understand themselves.

“We must cultivate women, who are the educators of the human race, else the new generation cannot accomplish its task.”

He saw women’s role as going far beyond the home.

The Froebel Web explains: “The women who trained as kindergarten teachers gained economic independence and a respected role in the community.”

Initially they were trained within the kindergartens. Many then went on to set-up their own establishments and train others. Women were primarily responsible for the spread of kindergartens across Europe, Russia and the United States.

Friedrich was aware of his own limitations, particularly in terms of passing on his ideas.

He believed in other people’s ability to carry the ideas forward. Drawing on his knowledge of nature, he recognised that some things took time. He wrote:

“The last word of my theory I shall carry to my grave, the time is not yet ripe for it.

“If three hundred years after my system of education is completely and according to its real principle carried through Europe, I shall rejoice in heaven.

“If only the seed be cast abroad, it’s springing up will not fail nor the fruit be wanting.”

Friedrich Froebel planted many seeds. Some have come to fruition.

Providing gardens for children, he helped many people to find and follow their passion in life. You can discover more about his work at the Froebel Web:

[…] Learn more about the man who started it all by clicking here. […]

[…] Friedrich Froebel […]

Was there a Froebel insitutute in South West London an was it run by the RSCJ (Sacred Heart9 nuns – if so, into which college Roehampton? – Strawberry Hill?

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Froebel_College