George Lyward was a charismatic educationalist who lived between 1894 and and 1973. He is best known for achieving outstanding results at Finchden Manor, a therapeutic community for disturbed boys.

I was fortunate to spend some time learning from him when I was running therapeutic communities.

Bus loads of social workers travelled to Finchden, which was located near Tenterden in Kent, to seek the secret of his success. Walking around the ramshackle huts, they saw boys playing guitars, kicking footballs, tending gardens and, in some cases, engaged in study.

Finally the visitors crammed into the large hall and bombarded George with questions.

“What therapy do you believe in,” they asked. “What is the staff’s role? They seem to do little except watch the boys.”

“You are right, they watch the boys,” said George. “Watching is one of the hardest things to do in life. Our staff watch the boys painting, mending cars, playing music, helping each other or whatever. They look for when the boy ‘comes alive’. They then nurture the boy’s talent and help them to shape their future life.”

Philosophy and Background

George Lyward’s work reached a wide audience in 1954, with the publication of Michael Burn’s book, Mr Lyward’s Answer. Visitors to Finchden saw the physical chaos, but also something deeper. Some called it ‘poetry’.

George – affectionately known to all as the ‘Chief’ – created an environment in which troubled boys were able to heal themselves. Almost 50% of the boys managed to steer clear of future state care.

These were excellent results, considering the deep seated nature of some of their problems. On the other hand, however, there were youngsters who continued to get into trouble, some going on to a life of crime.

Nevertheless, Finchden provided a light in the darkness for many young people. Here is a summary of the Memorial Address given by John Prickett at St. Martin’s in The Field, in October 1973.

George grew up in London, near Clapham Junction station. His father was an opera singer, but soon left the family home and seldom returned. His mother was a primary school teacher who, to make ends meet, lived with her sisters. George grew up with his mother, two aunts and two sisters.

Contracting poliomyelitis early in life, he had a weak leg, which laid him open to bullying. Channelling his energy into studies, he won a scholarship to Emanuel School, a public school in Battersea. Becoming a prefect, he was put in charge of the lower fifth, known as the ‘toughs’. He then became aware of his ability to get on with ‘difficult’ boys.

Leaving Emanuel, George worked in two preparatory schools and then pursued a choral scholarship at Cambridge. He loved his time at the university, taking the lead role in many musical productions. Studying to become a parson, he changed his mind two weeks before his planned ordination.

He went on to a series of teaching posts but, in 1928, suffered a serious breakdown following the breaking of an engagement to marry. George then spent some time recovering in a nursing home. John Prickett writes:

“It was while he was recovering at this nursing home that Dr Crichton-Miller (who was treating George) asked him to help some boy patients of his. He was so successful in this that eventually, as the demand for his help increased, he moved, at the suggestion of Dr Rees, to the farm of one of Rees’s old patients known as the Guildables, in Edenbridge, Kent. That was in 1930.

“By 1935 he had 20 boys there and was looking out for better and bigger accommodation. And so it was that he eventually moved to Finchden Manor, where (including a break for evacuation to the Welsh border during the war) he worked for 38 years.”

“It was in 1931 that he went from the Guildables with a friend for a few days holiday at Cromer. On entering the hotel courtyard he saw a group having tea outdoors, among whom was a girl with wonderful copper coloured hair. He later claimed that as soon as he saw her he said to his friend, ‘There is my wife.’ And so it proved to be.

“And so when he came to Finchden he had the support of a wife gifted in many remarkable ways whom he has rightly described as being ‘of heroic stature’. Her untimely death, and the tragic illness which led up to it, deprived Finchden of a source of warmth, colour and gaiety for which she will always be remembered with affection.

“Finchden has been described as one of the most important educational experiments of the century and has certainly had a considerable influence upon official policy concerning the treatment of disturbed adolescents, both in this country and abroad. (George Lyward’s work) was recognised by the award of the O.B.E. in 1970 and by the invitation he so much appreciated to ‘preach’ in Westminster Abbey in 1971.”

Principles

George had the ability to immediately reach young people, especially those who were ‘fighting themselves or fighting the world’. Finchden provided a sanctuary where there was little point in fighting anybody. Once the boys experienced this realisation – and the feeling of others caring for them – they could get on with their lives.

Let’s explore some of the principles that were followed at Finchden.

Connecting with troubled boys.

Tom Robinson, the musician and radio presenter, explains his own introduction to Finchden, particularly how George Lyward immediately connected with him.

“One night in the winter of 1966 I swallowed a handful of pills in a boarding school dorm to try and end my life, having fallen hopelessly and unrequitedly in love with another boy.

“Back then homosexuality was still punishable by four years in prison and at 16, awash with hormones and self-loathing, I’d rather have died than admit to anyone who and what I truly was.”

“My subsequent spell in a clinic with tests, sedatives, antidepressants and psychoanalysis did little to improve my frame of mind. Today my despairing father was driving me through the Weald of Kent towards my last hope – an interview at Finchden Manor.

“At the very edge of Tenterden a curving gravel drive hedged in with overgrown yew gave suddenly onto the courtyard of a battered Jacobean manor house.

“Even as we parked, several unshaven faces stared out through dirty leaded windows that had been broken and mended again and again. They were framed with hair like – not Beatles or even Rolling Stones – but like, well, girls. It was January 1967.”

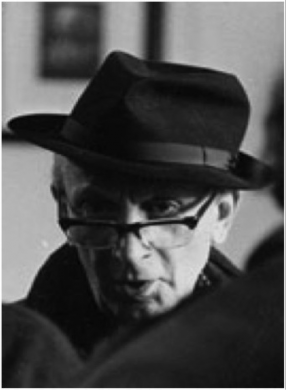

“As George Lyward stepped forward to take my hand in both of his, and hold it for longer than felt comfortable, I became aware of a formidable charisma. ‘Hello,’ he said, looking at me piercingly for a moment over his glasses before adding softly ‘You’re very lonely aren’t you?’

“I practically burst into tears on the spot. After all the drugs and psychiatric nonsense, here at last was someone who understood, saw at once where I was hurting and knew how to make the hurting stop. I instinctively trusted him with my life.”

“That lunchtime we sat jammed rowdily together on wooden benches at trestle tables. Hygiene was basic yet the food was edible, the shouting banter good natured, and the atmosphere vigorously alive. It couldn’t have been more different from the Quaker boarding school I’d just left.

“At the end of my visit, Mr Lyward told me Finchden was currently full with a long waiting list, and in any case didn’t normally take boys as ‘sick’ as me. Then he asked quite suddenly: ‘Do you want to come?’ I seized the lifeline, and stayed six years.”

Practicing the art of ‘losing time’, being in the moment and experiencing life.

Time seemed to stand still at Finchden. Certainly there was a schedule: regular meals each day, animals to be fed and, most importantly in the Chief’s eyes, stage plays to be performed – either for others in the community or for the local neighbourhood. Tom Robinson explains that:

“Most of us who came to Finchden had been excluded from school for one reason or another. For some it was an alternative to borstal, mental hospital or – as in my own case – simple extinction. None of us were much interested in each other’s past lives – all that counted was the kind of person you were in the here and now.”

The boys were given ‘a respite’. Nobody was forcing them to do anything – so they could experiment without unreasonable expectations from authorities.

But – and it was a big ‘but’ – people quickly understood the consequences of their actions. If a new boy decided to ‘fight’ by throwing bricks through the dorm windows, they and their room mates froze in the wind. If the dishes were not washed up, nobody had hot food.

The act of living together – and seeing the effects of one’s actions – was real reality therapy. Cast free from ‘threats’ – past or future, real or imagined – the boys began to develop their own rhythms.

They learned to fully experience life in the moment and, as a consequence, follow their true selves. Their future lives may be unpredictable, but this sense of being real provided a good start.

Providing many different forms of stimulation – including ‘paradoxical interventions’.

Despite its timelessness, Finchden was full of surprises. Tom Robinson explained that there might be breakfast outdoors, strawberries for tea, a trip to the seaside, a formal dance, months of preparation for a Shakespeare play or even double pocket-money one week.

One morning, out of the blue, there might be an instruction for a ‘command performance’. The boys were expected to put on a cabaret to be delivered that night.

George Lyward was a master of ‘paradoxical interventions’ – actions that didn’t appear to make sense – but which had a profound effect. When I met him at Finchden, he talked about a boy who consistently turned up late for breakfast. (Despite being tolerant on other issues, George was insistent on meal times being observed properly.)

The boy who arrived late was worried about the reaction, only to be met Mr Lyward saying: “Give this boy a hot breakfast.” (A rare treat.) “In fact, give him double bacon and eggs.” The boy was never late again. John Prickett explains why Lyward used such an approach.

“He saw that the loosening up of compulsive patterns and reactions could be helped by paradoxical treatment which surprised, even shocked, and forced the boy to ask himself questions.

“Whereas on arrival a boy knew what reaction to expect to his own rebellious and antisocial behaviour, he would be startled and bewildered by what some have called ‘paradoxical’ reactions, so unexpected as to disturb quite deeply the fixed patterns formerly ingrained.”

“When a boy had been absent without permission for several days causing many hours of additional work for Lyward and the staff in trying to trace him and to allay the anxiety of parents, not only would he be fetched by car, if necessary from considerable distances, but on arrival would be warmly welcomed back, and opportunities would be sought of giving him permissions or articles of clothing or whatever, for which he had previously been asking without success.”

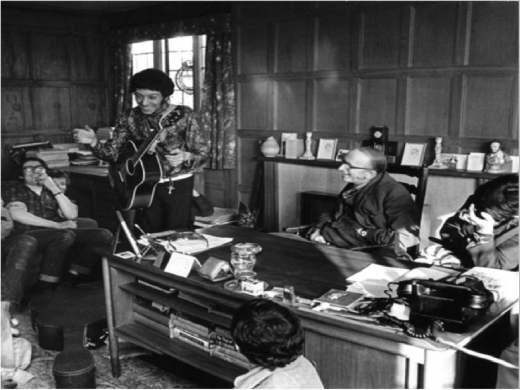

(Finchden produced an interesting alumni, several of whom went on to become musicians. One of these, Alexis Korner, is pictured below revisiting the community.)

Practice

Did George Lyward’s methods work? The community achieved a ‘success rate’ of almost 50%, but it also had strong critics. Finchden certainly had an advantage over the state system.

It chose boys who had the ability to gain insights into their situations. For almost 40 years, however, it helped such youngsters to develop a more enriching life.

George Lyward’s legacy had a profound effect on other pioneers in education and therapy. The Peper Harow residential community in Godalming, Surrey, for example, adopted many approaches used at Finchden.

Led by Melvyn Rose and founded in 1970, it gained an international reputation for outstanding work with disturbed adolescents. For over 20 years, it provided a therapeutic environment for teenagers who had suffered abuse. Melvyn’s book, Transforming Hate to Love, catalogues Peper Harow’s excellent results.

Modern society spends enormous amounts of money caring for the perpetrators and victims of crime and family breakdown. The approaches adopted by Finchden and other communities may have been unorthodox.

But they also produced financial benefits; such as society not having to pay for a lifetime of care for some people. Talking about troubled teenagers, Mr Lyward’s view was:

“Let them have their childhoods. Let them do all the things they want to do as children. If they don’t do them now, they’ll do much worse things later.”

Mr. Lyward’s approach had a profound impact on many young people’s lives. The language he used – and the way he connected with people – was different.

This was exemplified by a theatrical sketch presented by some boys at a public performance. One boy appeared dressed as George Lyward. Another as a prospective new boy arriving at Finchden. The dialogue went:

GL: And what can we do for you, my boy?

Boy: Please … I want to come to Finchden.

GL: And what is the matter with you, my boy?

Boy: I’ve got schizophrenia. (Bursts into tears.)

GL: There, there, my boy. (Pats Boy vaguely on head.) You shall come to us.

Boy: Oh, thank you, sir! What shall I bring?

GL: Bring? Bring nothing.

Boy: Nothing, sir?

GL: Well – ah – my boy – bring a toothbrush. And – ah – if you have one, bring a dream.

You can find out more about George Lyward’s work at:

Thank you for sharing this post, as an ex-member of Peperharow I found it extremely interesting. I will always be grateful for the wonderful George Lyward & Melvyn Rose for creating the opportunity to heal & live a life.

I was a pupil at Finchden Manor between 1953_1956. Mr Lyward was the most outstanding human being that I ever encountered. I came from a very impoverished background and had become a very unpleasant person.when I left Finchden I had transformed into what I thought was a very useful member of society and this was undoubtably due to the attention that Mr.Lyward and his staff gave me.I will be eternally grateful to this wonderful man.