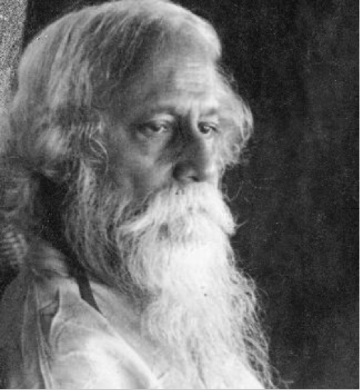

Rabindranath Tagore is best known as a writer and poet, but he was also an educational pioneer. Concerned about the over-industrialisation of education, he founded a school at Santiniketan. This was dedicated to encouraging children to develop as whole human beings. He wrote:

“But for us to maintain the self-respect which we owe to ourselves and to our creator, we must make the purpose of education nothing short of the highest purpose of man, the fullest growth and freedom of soul.”

Tagore never wrote down his complete philosophy of education. He provided glimpses, however, in a lecture he gave in America called My School. You can find the full text at:

http://www.gyanpedia.in/Portals/0/Toys%20from%20Trash/Resources/books/readings/03.pdf

Philosophy and Background

Rabindranath also wrote a biting satire on conventional schooling called The Parrot’s Tale. This showed how a parrot was to be ‘educated’. He was locked in a cage, denied food and water and had theories written on paper rammed down its throat. Tagore had different views of education. For example, he believed that:

People learn best when they experience real life – such as being connected to nature.

They often learn on a subconscious level when surrounded by stimulating influences. They learn from interesting people, art, music, dance, creativity, ideas and the humanities.

People gather strength from understanding their own heritage.

They also learn, however, from exploring and appreciating the best in other cultures.

People learn by creating and doing – rather than being force-fed abstract concepts.

They then develop their own aesthetic, intellectual and other qualities.

Tagore’s views on education were strongly influenced by his own background. So let’s explore the influences that shaped his philosophy.

(Please note. The school he founded at Santiniketan is sometimes spelt as Shantiniketen in various documents from different sources. When quoting the documents, I will use the spelling that is used by the respective authors.)

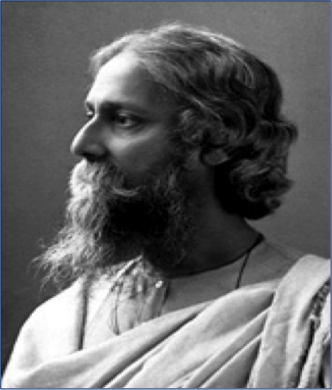

Beginnings

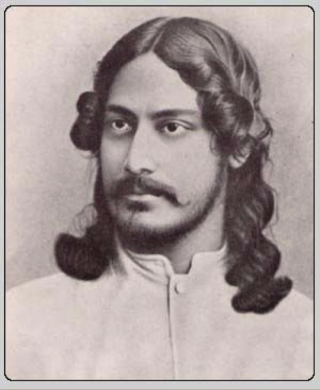

Tagore as a student in London

Rabindranath was born on May 1861 into a notable Brahmin family in Calcutta. His parents were Debendranath and Sarada Devi – and he was the ninth son of 14 children.

The family had a strong pioneering and cultural history. Rabindranath’s ancestors included people who had, for example, taught law in London; introduced orchestral music to India; been patrons of European art; mastered many languages; studied at the Royal Academy; founded universities and theatres; been wealthy landowners; acted as presidents of the British India Association and created their own forms of spiritual pursuits.

Some family members played a strong part in the Nationalist Movement and fought for the rights of people in Bengal.

(The family name ‘Tagore’ is an Anglo version of ‘Thakur’. This is derived from ‘Thakurmashai’ – or ‘holy sir’ – a name given out of respect to a Brahmin family.)

Rabindranath – whose nickname was Rabi – grew up surrounded by artists, music, drama and people from different cultures. Perhaps this explains the beliefs he espoused later about the importance of subconscious learning.

Many of his siblings went on to perform outstanding work in the arts, mathematics and other fields. He initially attended the Oriental Seminary School, but found this limiting, so studied at home with private teachers. The Bharat Image website continues the story, explaining:

“After undergoing his upanayan (coming-of-age) rite at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta on February 14, 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father’s Santiniketan estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There,

“Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of Kalidasa … Tagore began writing poems at the age of eight; he published his first substantial poetry in 1877 and wrote his first short stories and dramas at age sixteen.”

Tagore studied at other schools, but he remained wary of conventional education. He much preferred the joy of pursuing artistic work in a stimulating environment – something he was able to create in the school he later founded.

Creative work

Rabi’s father wanted him to become a barrister. Travelling to England, he studied at a school in Brighton, before going on to University College, London. Recalled for an arranged marriage, he never finished his degree. Tagore married Bhabatarini Devi in 1883. (Her name was later changed to Mrinalini Devi.)

He was twenty-two, she was just 10-years-old. They had five children, only one of whom survived into adulthood. Mrinalini died in 1902. He composed a collection of poems called Smaran (In Memoriam) which were dedicated to her.

Rabi and Mrinalini began managing his family’s estates in Shelidah, which is now part of Bangladesh. He then moved to Santiniketan in West Bengal, where his father had founded an Ashram – a spiritual sanctuary. This also became the location for his school. Rabi received income from his inheritance, sales of property and some royalties.

Over the next 40 years Tagore produced a remarkable body of creative work. This included poems, plays, music, paintings and social experiments.

He also wrote the national anthems of both India and Bangladesh. During this time he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature and a Knighthood from Britain. (He tried to revoke the Knighthood after the massacre at Amritsar.

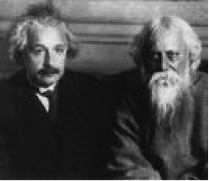

A great traveller, he visited over 30 countries on five continents. This enabled him to meet people such as Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Mahatma Gandhi, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells.

Tagore and Einstein

Towards the end of his life he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University, the ceremony being held at Santiniketan. Here is an overview of his creative work written by Kanad Malik.

“Tagore was a prolific writer and composed about seven thousand poems, songs, short stories, novels, dramas, musicals letters and essays in all. These are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh.

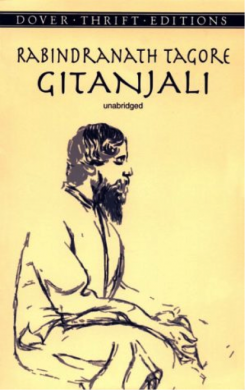

“In his late years, Tagore started painting also and initiated a new style of the art. Tagore won the Nobel Prize Literature in 1913 for the English version of his collection of Bengali poems, Geetanjali (an offering in songs).

“His citation read that he was being awarded the prize: ‘because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the literature of the West’.”

“He is remembered for expressing and analyzing through his extensive literature all possible tenets of human characters and emotions. This is why his work is and will continue to remain relevant to us for times to come.

“Tagore’s philosophy and writings were extremely important elements in the renaissance of Bengal and India at large in the early twentieth century and shaped the Bengali literature and culture in a modern, progressive mould.”

“Most of Tagore’s work was written at Santiniketan the small town that grew around the school he founded, and he not only conceived there an imaginative and innovative system of education, but through his writings and his influence on students and teachers, he was able to use the school as a base from which he could take a major part in India’s social, political, and cultural movements.”

“The profoundly original writer, whose elegant prose and magical poetry Bengali readers know well, is not the sermonizing spiritual guru.

“Tagore was not only an immensely versatile philosopher-poet; he was also a great short story writer, novelist, playwright, essayist, and composer of songs, as well as a talented painter whose pictures, with their mixture of representation and abstraction, are only now beginning to receive the acclaim that they have long deserved.

“His essays, moreover, ranged over literature, politics, culture, social change, religious beliefs, philosophical analysis, international relations and above all, humanism.”

You can read the full piece at:

Rabindranath continued to travel the world and meet leading figures. Some who had hailed his first work began to criticise him, but he remained revered in many quarters. He suffered several severe illnesses during the last years of his life, losing consciousness for long periods of time.

Rabi died in August 1941 at his home in Calcutta – the house where he was born in 1861. He is remembered for many creative works, such as his poetry, stories and paintings. But let’s take a closer look at his educational work at Santiniketan – the ‘abode of peace’.

Santiniketan

Rabi aimed to create a stimulating sanctuary. He wanted a place where children were connected to nature – yet also able to experience the best from their own and other cultures. Looking around the family estate, he chose to base the school at Santiniketan. He later wrote:

“I selected a beautiful place, far away from the contamination of town life … I knew that the mind had its hunger for the ministrations of nature, mother-nature, and so I selected this spot where the sky is unobstructed to the verge of the horizon.

“There the mind could have its fearless freedom to create its own dreams and the seasons could come with all their colours and movements and beauty into the very heart of the human dwelling.”

You can find more information about the environment at Santiniketan – and the present day university there – at:

Rabi believed in holding open-air classes. Children could learn from being connected to the rhythms of nature, rather than being separated from these life-forces. It was vital to be aware of Mother Earth – the giver of life – otherwise numbness could come to the soul.

Recalling his own childhood, Rabi was anxious to expose children to a rich tapestry of ideas, people, music, art, dance and other stimulation. They should also be able to express themselves, rather than be seen as empty vessels to be stuffed with facts.

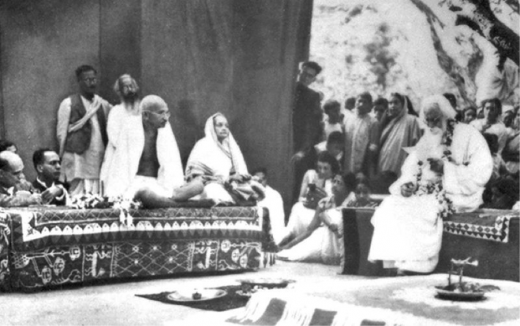

Gandhi and Tagore at Santiniketan in 1940

Satyajit Ray, the great Indian film-maker, began studying at the school in 1940. Reluctant to attend at first, he later wrote:

“I consider the three years I spent in Shantiniketan as the most fruitful of my life … Shantiniketan opened my eyes for the first time to the splendours of Indian and Far Eastern art. Until then I was completely under the sway of Western art, music and literature. Shantiniketan made me the combined product of East and West that I am.”

Amartya Sen, who won a Nobel Memorial Prize ‘for his contributions to welfare economics’, was actually born on the campus at Santiniketan. His maternal grandfather taught there, whilst both his mother and he studied at the school. He later wrote:

“I am partial to seeing Tagore as an educator, having myself been educated at Shantiniketan. The school was unusual in many different ways, such as the oddity that classes, excepting those requiring a laboratory, were held outdoors (whenever the weather permitted).

“No matter what we thought of Rabindranath’s belief that one gains from being in a natural setting while learning (some of us argued about this theory), we typically found the experience of outdoor schooling extremely attractive and pleasant.”

“Academically, our school was not particularly exacting (often we did not have any examinations at all), and it could not, by the usual academic standards, compete with some of the better schools in Calcutta.

“But there was something remarkable about the ease with which class discussions could move from Indian traditional literature to contemporary as well as classical Western thought, and then to the culture of China or Japan or elsewhere.

“The school’s celebration of variety was also in sharp contrast with the cultural conservatism and separatism that has tended to grip India from time to time.”

The school at Santiniketan evolved into a wider campus, which eventually became the Visva-Bharati University. Tagore envisaged it as a national centre for the arts, whilst also providing a home for speakers, artists, dancers and people from many nations. The mission he outlined remains to this day. You can find it at:

“Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India’s obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India’s right to accept from others their best.”

Tagore continued to experiment, co-operating with Leonard Elmhirst to set up an Institute of Rural Reconstruction. Elmhirst, who travelled with Rabi for several years, became the project’s first director. He also cited Tagore as his inspiration for, together with his wife Dorothy, founding the community at Dartington Hall, Devon, in 1925. (See link below.)

Tagore continues to be revered for his contribution to Asian culture: but let’s take a closer look at the educational principles he followed to encourage people to develop their talents.

Principles

Tagore’s believed that it was vital to recognise and follow the eternal rhythms in the world. Writing in A Poet’s School, he explained:

“We have come to this world to accept it, not merely to know it. We may become powerful by knowledge, but we attain fullness by sympathy. The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.”

“But we find that this education of sympathy is not only systematically ignored in schools, but it is severely repressed.

“From our very childhood habits are formed and knowledge is imparted in such a manner that our life is weaned away from nature and our mind and the world are set in opposition from the beginning of our days. Thus the greatest of educations for which we came prepared is neglected, and we are made to lose our world to find a bagful of information instead.”

“We rob the child of his earth to teach him geography, of language to teach him grammar. His hunger is for the Epic, but he is supplied with chronicles of facts and dates … Child-nature protests against such calamity with all its power of suffering, subdued at last into silence by punishment.”

People learn best when they experience real life, felt Rabi, particularly when connected with nature. Building on this base, he pursued the following principles to help people express their talents.

People learn on a subconscious level when surrounded by stimulating influences – such as interesting people, the arts and ideas.

We all learn from our environment – particularly the feelings, sights, sounds and impressions we absorb in our family and school.

The best learning places provide stimulation; the worst deaden the soul. Looking back at his own family, Tagore realised how much he had learned from being exposed to art, music and other influences.

So he invited artists, dancers and many different speakers to share their work at Santiniketan. This created a rich community. Students were bound to learn – even if it was on a subconscious level. They would then carry these impressions with them into the future.

People gain strength from exploring and expressing their own heritage and other cultures.

Tagore believed it was vital for people to begin learning in their own language, such as Bengali rather than English. They could also draw strength from taking pride in their own heritage. At the same time, however, there was much to learn from other cultures.

Perhaps this again reflected his upbringing. Rabi described his own Bengali family as the product of: ‘a confluence of three cultures: Hindu, Mohammedan, and British’. Kathleen M. O’Connell explains how these themes ran through his work. She writes:

“The meeting-ground of cultures, as Rabindranath envisioned it at Visva-Bharati, should be a learning centre where conflicting interests are minimized, where individuals work together in a common pursuit of truth and realise ‘that artists in all parts of the world have created forms of beauty, scientists discovered secrets of the universe, philosophers solved the problems of existence, saints made the truth of the spiritual world organic in their own lives, not merely for some particular race to which they belonged, but for all mankind.’”

“Rather than studying national cultures for the wars won and cultural dominance imposed, he advocated a teaching system that analysed history and culture for the progress that had been made in breaking down social and religious barriers.

“Such an approach emphasized the innovations that had been made in integrating individuals of diverse backgrounds into a larger framework, and in devising the economic policies which emphasized social justice and narrowed the gap between rich and poor.

“Art would be studied for its role in furthering the aesthetic imagination and expressing universal themes.”

You can read Kathleen’s excellent article at:

People learn by creating and doing – rather than being force-fed abstract concepts.

They then develop their own aesthetic, intellectual and other qualities. “Every child comes with the message that God is not yet discouraged of man,” wrote Tagore. He also wrote: “Love does not claim possession, but gives freedom.”

Education could enable people to express their true selves, providing they were enabled to create. Students at Santiniketan were encouraged to write, act, dance, paint and find other ways to express themselves.

Tagore warned against the industrialisation of education – an approach adopted by many governments. He channelled this concern into a short story called The Parrot’s Tale.

This explained how a king’s servants attempted to educate a parrot. Locking it in a cage, they denied it food and water. Writing knowledge on sheaves of paper, they shoved these down its throat. Here is an extract from the story. You can find the original at:

The bird died – no one knew when.

The King called the nephew and asked: “Dear nephew, what is this that I hear?”

The nephew said: “Your Majesty, the bird’s education is now complete.”

The King asked: “Does it still jump?”

The nephew said: “God forbid.”

“Does it still fly?”

“No.”

“Does it sing any more?”

“No.”

“Does it scream if it doesn’t get food?”

“No.”

The King said: “Bring the bird in. I would like to see it.”

The bird was brought in. With it came the administrator, the guards, the horsemen. The King felt the bird. It didn’t open its mouth and didn’t utter a word. Only the pages of books, stuffed inside its stomach, raised a ruffling sound.

Tagore believed education could enable people to learn from different cultures and express their talents. They would then be more ready to choose their route in life. He wrote:

“Man’s abiding happiness is not in getting anything but in giving himself up to what is greater than himself, to ideas which are larger than his individual self, the idea of his country, of humanity, of God.”

Practice

So what have been the effects of Tagore’s educational work? Many see him as contributing to the spirit embodied by pioneers such as Pestalozzi, Froebel, Dewey and Montessori.

Some of his views were later incorporated into learning communities such as Dartington Hall. The Visva-Bharati University continues to flourish, as do many of his ideas. Rabi selected as its motto the Sanskrit verse, Yatra visvam bhavatieka nidam. This means: “Where the whole world meets in a single nest.”

Kathleen M. O’Connell also emphasises the value of his contribution. She writes:

“Tagore’s educational efforts were ground-breaking in many areas. He was one of the first in India to argue for a humane educational system that was in touch with the environment and aimed at overall development of the personality.

“Santiniketan became a model for vernacular instruction and the development of Bengali textbooks; as well, it offered one of the earliest coeducational programs in South Asia.

“The establishment of Visva-Bharati and Sriniketan led to pioneering efforts in many directions, including models for distinctively Indian higher education and mass education, as well as pan-Asian and global cultural exchange.”

“One characteristic that sets Rabindranath’s educational theory apart is his approach to education as a poet. At Santiniketan, he stated, his goal was to create a poem ‘in a medium other than words.’

“It was this poetic vision that enabled him to fashion a scheme of education which was all inclusive, and to devise a unique program for education in nature and creative self-expression in a learning climate congenial to global cultural exchange.”

“Don’t limit a child to your own learning,” said Tagore, “for he was born in another time.” He also said: “We come nearest to the great when we are great in humility.”

Rabi’s work has enabled many people to appreciate life, be more humble and give their best to the world.

Don’t limit a child to your

learning, for he was born in another time. About the quote, could you provide source please! I want to know in which poem or article it was mentioned by Tagore.