Thomas Armstrong has helped thousands of people to find their natural talents. His books are inspiring and also extremely practical. They enable readers to find and develop their intelligences.

Whilst his books often focus on children, the insights he provides can be used by people in all walks of life.

Paying great tribute to Howard Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences, Thomas offers practical tools for translating these concepts into concrete actions.

His books are full of hope and down-to-earth tips. They provide a vast repertoire of ideas for every parent, teacher, manager, leader and coach. You can discover more at his web site and blog listed below:

http://institute4learning.com/index.php

Philosophy and background

Thomas believes that every child is gifted. He says:

“Each child comes into the world with unique potentials that, if properly nourished, can contribute to the betterment of our world.”

The key is to find and develop their unique talents. I first came across his ideas in the book In Their Own Way, which he begins by saying:

“Six years ago I quit my job as a learning disabilities specialist. I had to. I no longer believed in learning disabilities.

“It was then that I turned to the concept of learning differences as an alternative to learning disabilities.

“I realised that the millions of children being referred to as learning disabled weren’t handicapped, but instead had unique learning styles that the schools did not understand.”

“Everyone has (the different) kinds of intelligence in different proportions.

“Your child may be a great reader but a poor math student, a wonderful drawer but clumsy out on the playing field. Children can even show a wide range of strengths and weaknesses within one area of intelligence.

“Your child may write very well but have difficulty with spelling or handwriting, read poorly but be a superb story-teller, play an excellent game of basketball but stumble on the dance floor.”

An Educational Odyssey

One of Thomas’ books is called The Human Odyssey. This charts what he sees as the 12 stages of life – more of which later.

Thomas grew up in Fargo, North Dakota which he describes as an “uncomplicated place to live.” His father was a doctor who suffered a nervous breakdown which incapacitated him for many years.

Sometimes this created tensions, however, which affected the family. The family home was also destroyed by a tornado, which increased the overall level of insecurity.

Thomas describes himself as a relatively ordinary child, but says: “I was always wondering about the ultimate questions of life.”

So how did he get into education? Thomas says that he may have been unconsciously influenced by an aunt who became a director of the Amsterdam International School. He also had teachers who treated him as an individual and fed his love of learning.

Looking back, he remembers being artistic – drawing, painting and creating collages – then switched to becoming verbal. Thomas went on to have a successful educational career – teaching right through from primary to doctoral level.

During this time, however, he became increasingly passionate about the importance of encouraging the strengths within every child.

He began producing many books and videos on the topic. These included The Myth of the A.D.D. Child and Awakening Your Child’s Natural Genius.

Thomas has now over 1 million books in print. He also says that, over the past decade or so, he has rediscovered his artistic side – restarting drawing and painting.

Talking with Kelly Jad’on, he explained this may be why he is so passionate about children who are labelled as being ‘learning disabled’ (LD) or having ‘attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

He feels they may be artistic, but that this side of their personality is ignored. Looking back on his own life, he says:

“I was a late bloomer and didn’t find my marriage partner or career until my late thirties .

“So now that these are going along pretty well, I can focus on more on developing other potentialities that didn’t get a chance to develop during my early adulthood, like my art and novel-writing.”

Thomas says that his writing is motivated by the desire to ensure that every child gets a chance to fulfil their potential. His books help teachers spot each individual’s strengths and preferred learning styles.

They can then create enjoyable and effective lessons that give every child the opportunity to develop. So let’s explore some of his key ideas, starting with those in his book 7 Kinds of Smart.

People have

Multiple Intelligences

Thomas embraces much of Howard Gardner’s groundbreaking work on multiple intelligences. He has translated this philosophy into practical tools that people can use in their daily lives. So what is the story behind these intelligences?

Howard Gardner is a Harvard Professor who in 1983 published his pioneering book Frames of Mind.

This challenged the academic establishment by expanding the conventional number of intelligences measured by schools.

Such institutions tended to look for linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences. They paid little attention to other talents unless, for example, a person was outstanding at athletics or art.

Such an approach might be justified in institutions that aimed to recruit people who embodied such skills. But there were knock-on effects. This approach to measuring ‘intelligence’ was cascaded right through the education system.

Children who had other talents had great difficulty being recognised by the system.

Certainly each student must take responsibility for shaping their future, but this might be easier in an environment that encouraged their talents. Some were actually punished or ‘labelled’ because their natural abilities did not fit into the system.

Gardner’s book stated there were many intelligences. Since then he has expanded these to cover the following intelligences: interpersonal, spatial, linguistic, logical, musical, kinaesthetic, naturalist, existential and intrapersonal.

Gardner’s treatise was somewhat academic, as were the names he coined. He also later confessed to being deliberatively provocative by calling these intelligences rather than, for example, styles.

Gardner got his reaction. Academics debated the semantics, whilst practitioners translated the ideas into action in the schools.

Howard Gardner went on to publish a book that showed how the MI approach had been translated into practice. This was simply called Multiple Intelligences. By the start of the 21st Century many of his ideas had entered mainstream education.

Some educators understood the spirit behind the approach; others simply applied it as a tick-box system they must implement.

The phrase MI entered the educational system, but there was a need to reach a wider audience. This is where Thomas Armstrong came into his element.

Recognising your Smarts

One reaction to multiple intelligences was that the labels were complicated. Thomas’ book 7 Kinds of Smart showed how the theories could be translated into daily reality.

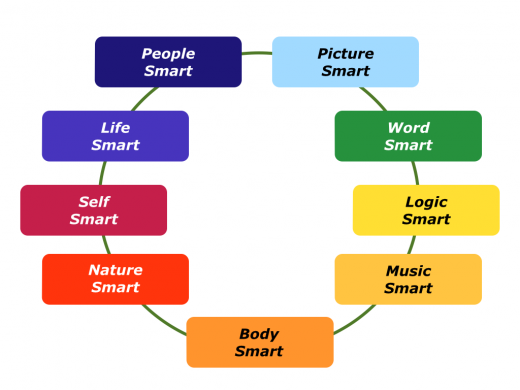

The various smarts overlap, of course, so it is good to bear this mind when identifying a person’s preferred style. Thomas’ book outlined seven smarts. Since then he has added two more smarts.

So let’s explore these talents that a person may demonstrate in their life and work.

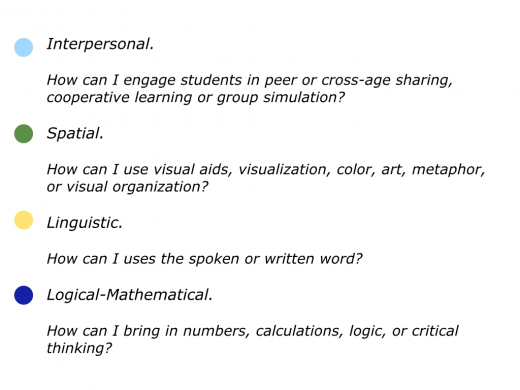

People Smart.

Such a person may be good at working with people. For example, they enjoy building relationships, encouraging others and social interaction.

They have strong empathy skills. Sometimes they sense what is going to happen in a group, for example, before it actually happens.

They can also be good at organising people and co-ordinating the strengths in a team. The best way to help them learn may be through conversations, role-plays, simulation and other activities involving people. People smart corresponds to what Howard Gardner called Interpersonal intelligence.

Picture Smart.

They may be good at working with pictures, images, drawing, colours, art, imagining or other forms of visual organisation. They often need to create or find visual images that enable them to retain information.

The best way to help them learn is by using these media. Picture smart corresponds to Spatial intelligence.

Word Smart.

They may be good at working with words, conversations, writing and languages. They enjoy speaking, story telling, explaining, using humour and teaching.

The best way to help them learn may be inviting them to use these skills through writing, presenting, speaking new languages and other verbal media. Word smart corresponds to Linguistic intelligence.

Logic Smart.

They may be good at elements of reasoning, gathering information and numbers. They enjoy thinking conceptually, seeing patterns and making connections.

The best way to help them to learn may be inviting them to solve problems – particularly in their areas of greatest interest – collect data, do experiments and present the information. Logic smart to what Howard Gardner called Logical-Mathematical intelligence.

Music Smart.

They may be good at creating and appreciating music. They also often think in sounds, patterns and ‘rhythms’. Some are sensitive to even the smallest sounds – which can be either helpful or distracting.

The best way to help them to learn is through music and, for example, helping them to see rhythms – patterns – in other areas of learning. Music smart corresponds to Musical-Rhythmic intelligence.

Body Smart.

They may be good at controlling their body movements, dancing, sports and managing materials successfully. They express themselves through movement – sometimes finding it difficult to sit still – and often have good hand-eye co-ordination.

The best way to help them learn is anything involved with movement or activities that evoke feelings. Such people have a strong muscle memory, being able to call on lessons they have integrated into their bodies. Body smart corresponds to Kinaesthetic Intelligence.

Nature Smart.

They are good at seeing rhythms in nature and have a feeling for living things. Here is a superb definition from Kathy Koch of what is called Naturalist intelligence. You can find the original at:

“Nature-smart children think in patterns and are usually able to compare and contrast easily … (They) usually enjoy collecting things according to shape, design, and texture … Children who are nature smart love to be outside.

“They may get dirty during every recess because they dig in dirt and pick up every rock and acorn … Attention is probably heightened when lessons have to do with animals, rocks, mountains, lakes, planets, and other things of nature.

Life Smart. (Existential Smart.)

Throughout history individuals have asked questions such as:

“Who am I? What do I want to do in my life? Why do I want to do it? How can I make it happen? When do I want to begin?”

People with existential intelligence gather knowledge and, in some cases, wisdom to enable themselves and others to explore and find answers to these questions.

They may also focus on the more spiritual aspects of existence and our purpose on the planet.

Self Smart.

Such people have a good understanding of themselves. They clarify their inner feelings, strengths and weaknesses.

They tend to think deeply about topics and can sometimes be quiet. They may feel uncomfortable being ‘graded’ by others, because it involves outside judgements about their own views.

They learn best by focusing on topics related to their own lives and experiences. Such people often prefer to work alone.

They like being given time and space to explore their own insights. Self smart corresponds to what is called Intrapersonal intelligence. Thomas has written:

“Intrapersonal children tend to be loners. Although they may seem very isolated and cut off from the world, they in fact take in a great deal of what they observe, and possess rich inner lives.

“They like going their own way – doing things in their own time. Fiercely independent, they can be very hard to deal with, if forced to learn in a specific way imposed from without.

“They need to be given choices about their learning. ‘Do you want to do a project on birds, or on dinosaurs? Do you want to study the problems on page 14, or page 16?’

“They do best with independent study, individualized projects and self-paced materials such as computer software programs.

“Ask them about their interests – they may be slow to warm up to you, but once trust has been established, they will share with you some of their hopes and fears, some of their dreams and visions.

“Provide them with opportunities to be alone with themselves; give them the tools they require to carry out their self-chosen learning activities, and make sure they have enough time to work at their own pace.”

Let’s move on to exploring some of the principles behind Thomas’s work.

Principles

Thomas wants to provide parents and teachers with tools they can use to encourage children to fulfil their talents.

His book The Best Schools shows how education can return to what he calls: “The great questions of human growth and learning.” These include:

How can we help each child reach his or her true potential?

How can we inspire each child and adolescent to discover his or her inner passion to learn?

How can we honour the unique journey of each individual through life?

How can we inspire our students to develop into mature adults?

For him, The Best Schools are prepared to address these issues. So let’s look at three principles that underpin his work with parents and educators.

Everybody has strengths

Thomas believes every person has gifts. Some people are able to express these talents without encouragement – but they are the exception. The key is to provide the environment in which a person’s gifts can blossom.

Certainly a caring school can enhance this growth, but the place to start is the family. Contributing to a series of tips for the National Parenting Center, Thomas suggests:

Become a Strengths Detective.

“One important key to helping your child succeed in school is to become a ‘strength detective’ at home!

“Make a list of all the wonderful things about your child. Include information about special talents your child may possess, such as musical or artistic abilities, positive qualities your child demonstrates, including attributes such as creativity, courage and curiosity.

“And don’t forget to list things that your child is really interested in, like sports, reading or science.

“Then spend some time with your child – going over the list, and talking about ‘positives’ in his or her life. Make sure to ask him/her what he likes best about himself or herself.

“Encourage your child to keep a scrapbook of photos, artwork, school papers and other items having to do with accomplishments and abilities in his life.

“You may be surprised to see what a difference these things make in your child’s general attitude. Research suggests that when children feel better about themselves at home, their ability to succeed in school improves at the same time.”

Thomas’ web site is full of practical ideas. Here are some of the many tips he gave in an article called:

50 Ways To Bring Out Your Child’s Best

Let your child discover her own interests. Pay attention the activities she chooses. This free-time play can say a lot about where her gifts lie.

Expose your child to a broad spectrum of experiences. They may activate latent talents. Don’t assume that he isn’t gifted in an area because he hasn’t shown an interest.

Share your work life. Expose your child to images of success by taking him to work.

Let him see you engaged in meaningful activities and allow him to become involved. Share inspirational stories of people who succeeded in life.

Provide a sensory-rich environment. Have materials around the home that will stimulate the senses: finger paints, percussion instruments, and puppets.

Keep your own passion for learning alive. Your child will be influenced by your example.

Share your successes as a family. Talk about good things that happened during the day to enhance self-esteem.

Listen to your child. The things he cares about most may provide clues to his special talents.

Praise your child’s sense of responsibility at home when she completes assigned chores. Give your child unstructured time to simply daydream and wonder.

Encourage your child to think about her future. Support her visions without directing her into any specific field.

Introduce your child to interesting and capable people. Be a liaison between your child’s special talents and the real world. Help her find outlets for her talents.

Avoid comparing your child to others. Help your child compare himself to his own past performance. Accept your child as he or she is.

You can find the complete article, which was first published in Family Circle in 1993, at:

Everybody can be helped

to find their strengths

Thomas provides many tips that teachers can use to enable students to find their talents.

Much of his early work was focused on children given labels such as LD (Learning Disabled), ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) or AD/HD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder).

How to work with such students? He points out that many great figures in history were labelled as having some kind of learning disability.

He cites individuals such as Thomas Edison, Winston Churchill, Pablo Picasso, Florence Nightingale and Charles Darwin.

While not claiming that everybody will rise to such heights, Thomas urges teachers to remember that:

“A hyperactive child is an active child. These young people often possess great vitality a valuable resource that society needs for its own renewal.

“As educators, we can make a big difference in the lives of these students if we stop getting bogged down in their deficits and start highlighting their strengths!”

Here are some tips that he gives to teachers for harnessing the energy of such youngsters.

Use music to calm or focus. Sometimes rock or rap music may paradoxically calm some kids down just as Ritalin (a stimulant) does.

Find the time when the child is most alert. Mornings are usually best for focused work, such as seat-work, lectures, etc.; afternoons are best for open-ended activities – such as projects, arts, cooperative groups, etc.

Provide a balanced breakfast. Research suggests that balancing protein with carbohydrates, such as eggs and toast, is better for helping foster focused activity than simply a carbohydrate breakfast – such as pastries and orange juice.

Emphasize a strong physical education program in the schools. Include aerobic activity, individual sports – such as swimming, walking – and martial arts.

Allow appropriate movement in the classroom. Give kids chores to do, allow them to use a squeeze ball to keep their hands busy while listening to the teacher talk, give them active projects that involve frequent changes of seating, teach skills using physical movement. For example, in group choral spelling, standing up on the vowels and sitting down on the consonants.

Use hands-on teaming. Give students frequent opportunities to build things with their hands.

Provide positive role models. Study the lives of great people who had difficulty with behaviour in school. Envision positive futures. Help students see roles and careers for themselves in the world that make use of their special talents and abilities.

Identify talents, strengths and abilities. Find out which combination of Howard Gardner’s eight intelligences each student has most highly developed and use that information to provide appropriate instruction.

Have consistent routines in the classroom and involve the students in them. For example, a student is selected to collect papers, to signal others to get ready for lunch, etc.

Hold class meetings. Use these meetings as opportunities to air grievances, work out interpersonal problems between class members, plan for parties, and share other feelings and thoughts about how the class is going.

You can find the complete list of ideas on Thomas’ web site at:

Bringing The Learning To Life

“I agree with the concept of multiple intelligences,” a teacher might say.

“But that adds to the complications when leading a class. How is it possible to cover all the intelligences when teaching a subject?”

Many teachers already reach the various intelligences by using different media.

For example, they may use ‘talk and chalk’; written exercises; working in pairs, trios and groups; students presenting ideas; role-plays; ‘learning by doing’; music; film clips and many other media.

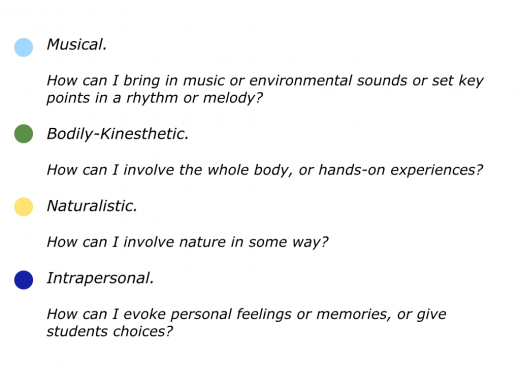

Thomas suggests asking the right questions, however, when planning a lesson. Here are some of his tips. They are from a piece called Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom, 2nd ed., Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2000.

Practice

So what have been the effects of Thomas’ work? His books have helped thousands of people to find their natural talents. They have been translated into 24 languages, including Spanish, Chinese, Hebrew, Danish, and Russian.

His ability to translate the philosophy of multiple intelligences into practical tips has enriched the lives of students and teachers in schools across the world.

Thomas has also opened people’s eyes to the strengths – rather than the shortcomings – of those given labels early in life.

His wrote Neurodiversity: Discovering the Hidden Strengths of Autism, ADHD, Dyslexia and Other Brain Differences.

His books show how the philosophy of multiple intelligences can be translated into daily practice. These have resulted in many more educators – and schools – identifying people’s strengths.

The educational approach he advocates enables people to identify their talents, learn how to learn, make good decisions and create a humane society. People are then more likely fulfil their potential.

Thomas continues his journey. Returning to one of his quotes at the start of this article, he said:

“Each child comes into the world with unique potentials that, if properly nourished, can contribute to the betterment of our world.”

He has helped to create environments in which people’s talents are nourished. As such, he has contributed towards the betterment of the world. Thomas aims to give even more on his ongoing odyssey.

Leave a Reply