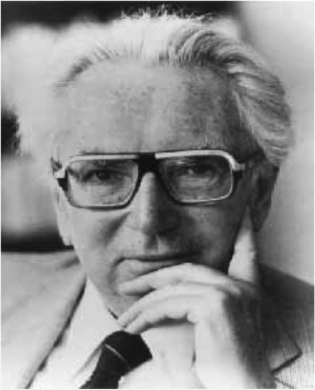

Viktor was an Austrian psychiatrist who lived between 1905 and 1997. He was a compelling speaker. This is a much-watched video of him giving a lecture in 1972.

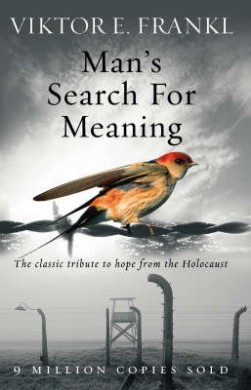

His work reached millions of people through his book Man’s Search For Meaning, which described his harrowing journey through the Nazi concentration camps. Surrounded by terror, he asked:

“How do you make sense of such madness?”

Frankl found that many of the survivors had something to live for beyond the immediate horror. They had a book to write, a relationship to rebuild or a dream to pursue. He later wrote:

“Everything can be taken from a man or a woman but one thing: the last of human freedoms to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Philosophy and Background

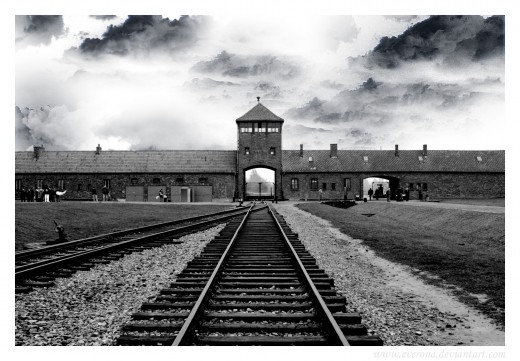

Chance played an enormous part in the death camps, of course, but each person faced choices each day. Viktor describes how it was vital to look alert and ready to work. New arrivals found the ordeal began when the railway trucks drew into the camp sidings.

Recalling his own experience, Viktor describes joining a long line which shuffled towards an SS Officer.

The Officer looked at each person and casually pointed to the left or the right.

“It was my turn,” writes Viktor. “Somebody whispered to me that to be sent to the right side would mean work, the way to the left being for the sick and those incapable of work …

“My haversack weighed me down a bit to the left, but I made an effort to walk upright.

“The SS man looked me over, appeared to hesitate, then put both his hands on my shoulders, I tried very hard to look smart, and he turned my shoulders very slowly until I faced right, and I moved over to that side.”

Ten percent were sent to the right and lived. Ninety percent were sent to the left and the ‘showers’. Viktor survived the Nazi camps, emigrated to America and practised as a psychiatrist. Working with suicidal people, he recognised the similarity between them and prisoners in the death camps.

He recalled two prisoners who talked of committing suicide. Both men used the typical argument: that they had nothing more to expect from life.

The challenge was to show the men that life was still expecting something from them. Viktor continues:

“We found, in fact, that for the one it was his child whom he adored and who was awaiting for him in a foreign country.

“For the other it was a thing, not a person. This was a scientist and had written a series of books which still needed to be finished. His work could not be done by anyone else, any more than another person could ever take the place of the father in his child’s affections …

“A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life.

“He knows the ‘why’ for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any ‘how’.”

Camp life showed that people do have a choice of action, said Viktor, and prisoners who lost faith in the future were doomed.

The definitive place to learn about his work is The Viktor Frankl Institute (see link below), but here is a brief overview of his biography.

http://www.viktorfrankl.org/index.html

Viktor was born into a Jewish family in Vienna, the cradle of psychoanalysis.

During his college years he showed a strong interest in psychology – going on to study medicine at the University of Vienna.

Specialising in neurology and psychiatry, he spent considerable time studying depression and suicide.

Viktor was 23 when he set-up cost-free counselling centres for students receiving exam results. These were spread across several cities and provided valuable support to students, some of whom were at risk of suicide.

Even before this time, however, he had begun using the term ‘Logotherapy’ – Logos being the Greek word for ‘meaning’.

During the 1920s and 30s he mixed with luminaries such as Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler and Wilhelm Reich, but he was already developing his own approach to working with patients.

Viktor became fascinated with each individual’s search to live a meaningful life. His ideas were put to the test when, in 1933, he headed a psychiatric ward for suicidal women.

This reinforced his belief that sometimes: “It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.”

The more we strive for ‘happiness’, the more it eludes us. We need to create a meaning for our lives – a vocation to follow, a person to help, a deed to do, a legacy to leave.

Happiness is often a by-product of doing our best during our time on Earth.

Viktor later quoted Albert Schweitzer, who said:

“The only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.”

Frankl started his own clinical practice in Vienna in 1937 and, one year later, the Nazi’s invaded Austria.

In 1940 he headed the neurological department of Rothschild Hospital, the only hospital treating Jews. He also began working on the manuscript that would later be published as The Doctor and the Soul.

Despite having a visa to enter the United States, Frankl chose to stay in Austria to care for his elderly parents.

He married his first wife, Tilly Grosser, in 1941, and the Nazi’s forced them to have their child aborted.

During the next years most of his family were deported to concentration camps where many, including his mother, father and wife, were murdered.

Frankl himself was imprisoned in several camps, one of which was Auschwitz.

Liberated by U.S. troops, he returned to Vienna to learn of the deaths of his loved ones.

Throwing himself into his work, Frankl became director of the Vienna Neurological Policlinic, a position he held for 25 years.

He reconstructed his book The Doctor and the Soul, the manuscript of which had been destroyed in the camps.

He also dictated – within the space of 9 days – Man’s Search for Meaning, which sold over 9 million copies.

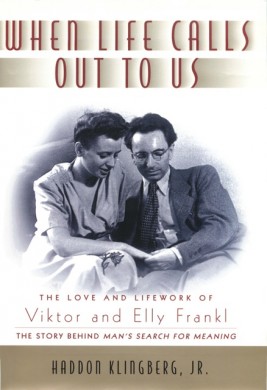

Frankl married his second wife, Eleonore, and they had a daughter, Gabriele. He spent the rest of his life travelling the world, teaching about Logotherapy and pursuing his chosen challenges.

He wrote more than 30 books, was an enthusiastic mountain climber and gained his pilot’s licence at the age of 67. Viktor died in 1997.

Principles

Viktor’s books pass-on the wisdom he gained from a life of service and suffering. Mans Search for Meaning, his most popular book, is written in two different styles.

The first part is highly personal and narrates his journey through the death camps. The second part provides a more philosophical introduction to Logotherapy.

(You can also gain an excellent insight into Frankl’s approach by viewing some of his interviews posted on YouTube. See links at the end of this article.)

Let’s explore some of the key principles that run through his philosophy.

People can choose their attitude.

Human beings want to feel in control. Time after time we hear people say: “But I had no choice.”

Based on his experience in the death camps, Frankl maintains that there is always one final freedom. We can choose our attitude towards events. He wrote:

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread.

“They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

People want to find and follow their personal sense of meaning.

Human beings long for a sense of purpose, said Frankl. He believed there were three ways to create meaning in life:

By doing a deed or creating a work.

By appreciating the experience of someone or something.

By choosing our attitude towards suffering.

He wrote: “Everyone has his own specific vocation or mission in life; everyone must carry out a concrete assignment that demands fulfilment.

Therein he cannot be replaced, nor can his life be repeated, thus, everyone’s task is unique as his specific opportunity to implement it.”

Frankl experienced this drive himself after losing the manuscript that summarised his life’s work.

He had sewn it into his coat lining, but lost it when transferred to Auschwitz.

During the terror he kept himself sane by spending nights reconstructing the book in his head, then on pieces of stolen paper.

People find ‘happiness’ as a by-product of following their meaning.

“Ever more people today have the means to live,” said Frankl, “but no meaning to live for.”

He saw that people were striving to achieve happiness through self-indulgence or gathering ‘outer’ things – such as possessions or status.

Writing in the preface to the 1984 edition of Man’s Search For Meaning, he explained:

“Again and again I admonish my students both in America and Europe: Don’t aim at success – the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it.

“For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself.

“Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it.

“I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge.

“Then you will live to see that in the long run – in the long run, I say – success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think of it.'”

Practice

What has been the effect of his contribution? During his lifetime Frankl obviously translated his own philosophy into clinical practice.

Beginning by providing counselling centres for students, he then spent many decades working with depressed and suicidal patients.

Logotherapy continues to be practiced across the world. The main centre of gravity is in Central Europe – particularly in Austria and Germany – whilst also being popular in South and North America.

Frankl’s greatest contribution, however, may be in spreading the concepts of ‘choice’ and pursuing one’s mission.

Virtually every self-respecting book on ‘purpose’ and ‘leaving a legacy’ pays homage to his influence.

Stephen Covey, for example, mentions Frankl as his ‘intellectual mentor’.

The power of Viktor’s message is now reaching a wider audience through media such as YouTube. (See link below.)

His ideas resonate with many of today’s young people who are seeking meaning in life. You can watch some of his interviews at:

http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=9EIxGrIc_6g

You may also want to read a superb book about Viktor and his second wife, Elly. When Life Calls Out To Us is written by Haddon Klingberg.

This provides an insight into their life together and how they embodied their ideas in practice.

Frankl always got to the heart of the matter. Speaking towards the end of his life, he said that, for humanity to survive, we needed to coalesce around a common purpose.

Faced by interviewers who asked what people should do when faced by the absence of faith, economic crises or global challenges, he went back to his famous saying.

Man is not free from his conditions, but he is free to take a stand towards his conditions.

We can choose our attitude and, if we wish, pass-on a better world to future generations.

Leave a Reply